This is the sixth post (and probably the last) in a series written by guests about CW’s penultimate novel, Descent Into Hell. Check out the others here.

Today’s post is by David Llewellyn Dodds.

David Llewellyn Dodds is editor of both the Charles Williams and John Masefield volumes in Boydell & Brewer’s Arthurian Poets series, and author of the entry on Williams and his fiction in the Dictionary of Literary Biography, vol. 153. He is currently editing Williams’s Arthurian Commonplace Book for publication.

David Llewellyn Dodds is editor of both the Charles Williams and John Masefield volumes in Boydell & Brewer’s Arthurian Poets series, and author of the entry on Williams and his fiction in the Dictionary of Literary Biography, vol. 153. He is currently editing Williams’s Arthurian Commonplace Book for publication.

Williams’s Pictures of the Sleeping and the Dead: A Survey

“The sleeping and the dead / Are but as pictures”, says Lady Macbeth, as she goes offstage to fake a crime scene. (Her regicide husband ̶ to whom Williams compares Wentworth in Descent into Hell (ch. 9) ̶ refused to do it, saying, “I am afraid to think what I have done / Look on’t again I dare not.”) Macbeth also includes a silent onstage Ghost.

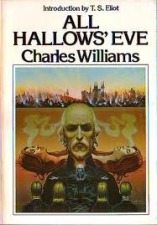

In Williams’s first dramatic work, The Chapel of the Thorn (1912), the murderous Amael asks, “Shall one alien or one dead / Be by a Faith he hath not known redeemed?”(II, 315-16). But 18 years pass before Williams first pictures “one dead” as a character in a major work: the murder victim, Pattison, in War in Heaven. The next major dead character is the nameless hanged workman in Descent into Hell (1937). But he is not the only one, there: in chapter 11, “The Opening of the Graves”, a “crowd” of others are pictured, too. (The weakly wailing “multitudes of the lost” in Williams’s only mature short story, “Et in Sempiternum Pereant” (1935), may foreshadow these.) Another seven years pass before Lester and Evelyn follow in All Hallows’ Eve (1944): both young women discover they are dead in the course of the novel’s first chapter. By then, however, Williams had also effectively invented, and uniquely resolved, the ‘zombie apocalypse’, in “Divites Dimisit” (1939) ̶ revised, it became the last Arthurian poem he published, “The Prayers of the Pope”, in The Region of the Summer Stars (1944).

In All Hallows’ Eve, Baptism explicitly saves Betty from becoming “one dead” like Pattison when her father attempts to murder her magically. Pattison had “thought the Lord had come to me and saved me”, but then seems to have despaired (ch. 14): Gregory says, of this “unhappy soul”, ‘it’ “returned to me and was utterly mine. It was willing to die when I slew it, and in the shadows it waits still upon my command” (ch. 15). Whether Pattison’s having “been saved” (ch. 13) was a return to the Faith in which he had been baptized earlier, is not clear. Nor is, I think, the baptismal status of any of the others: workman, “crowd”, Lester, Evelyn, or the “too-veritable ghosts” “of the dead whom the lords of empire had once slain, / […] images of old blockade and barricade, / children starved in sieges, prostituted women, / men made slaves or crucified” (“The Prayers of the Pope”, lines 109-12, 124). Are they among the “dead” or, instead, among those “who have fallen asleep in the hope of the resurrection and in faith on” Christ (to quote St. John Damascene)? They are all, in one sense or another, ‘unquiet’, and some have been made especially so by evil magical means.

By contrast, Williams pictures other characters whose baptismal status is probably safe to assume: “the dead lords of the Table” and others in a pair of Arthurian poems (or two versions of the same poem), the publications of which bracket that of Descent into Hell: “Taliessin’s Song of Lancelot’s Mass” (New English Poems, 1931), and “Taliessin at Lancelot’s Mass” (Taliessin though Logres, 1938). These are not certainly unquiet, though all do seem transformed in the course of the celebration. Mysteriously “drawn from their graves to the Mass” (1938), we might say that all seem there fed indeed, in contrast to “the grand gate of Gomorrah where aged Lilith incunabulates souls” (Descent into Hell, ch. 11).

In chapter 4 of Descent into Hell, we learn that John Struther “was martyred” (past perfect) under Queen Mary. He might well have prayed the collect for the First Sunday of Advent in the 1549 and 1552 Prayer Book for six to nine years before he went to the stake, as Williams probably prayed it for over 50 years: it begins, “Almighty God, give us grace that we may cast away the works of darkness, and put upon us the armour of light, now in the time of this mortal life”. Even as Struther was long dead to his descendants, Margaret and Pauline, they, being far descendants, must have been ‘not alive’ in the time of his mortal life. But chapter 10 shows Pauline and him alive together “at the table of exchange”, interacting.

In chapter 4 of Descent into Hell, we learn that John Struther “was martyred” (past perfect) under Queen Mary. He might well have prayed the collect for the First Sunday of Advent in the 1549 and 1552 Prayer Book for six to nine years before he went to the stake, as Williams probably prayed it for over 50 years: it begins, “Almighty God, give us grace that we may cast away the works of darkness, and put upon us the armour of light, now in the time of this mortal life”. Even as Struther was long dead to his descendants, Margaret and Pauline, they, being far descendants, must have been ‘not alive’ in the time of his mortal life. But chapter 10 shows Pauline and him alive together “at the table of exchange”, interacting.

The workman, Pattison, Lester, and Evelyn, seem more simply contemporary with the living, and seem able to change, to choose for better or worse, after the time of this mortal life. In Terror of Light (performed around Whitsun in May 1940), Williams gives the account in Acts 1:16-26 a striking addition when the Blessed Virgin says that the dead “Judas shall be glad of substitution and love it, […] His exclusion shall become his inclusion”. But, uniquely, in Williams’s last play, The House of the Octopus (1945), characters are killed in the course of the story and immediately rejoin the action. The first is Alayu, an island village’s youngest convert, who apostatizes from fear, and is struck dead in response to her clutching an invading soldier in her pleading. She soon returns, saying, “Just as I died, / I knew it was true,” and that she “was sent to ask” forgiveness. She is then further called on to bear the fear of her father in Christ, the missionary priest, Anthony. He had both condemned her apostasy and is himself willing to equivocate with Christianity and the invaders’ totalitarian ideology in his own fear of death. When he seems shocked to see and speak with her, “one of the dead”, she replies, “but you said / we were dead in Christ; there is nothing new in being dead.” The other converts agree. One speaks for all to the threatening Prefect: “We have been dead a long while”. They rejoice that martyrdom will seal their dying in Christ which replaced their earlier being dead in sin. After which, they are machine-gunned in numbers, to be raised again to close the play singing a hymn to the Holy Spirit.

The workman, Pattison, Lester, and Evelyn, seem more simply contemporary with the living, and seem able to change, to choose for better or worse, after the time of this mortal life. In Terror of Light (performed around Whitsun in May 1940), Williams gives the account in Acts 1:16-26 a striking addition when the Blessed Virgin says that the dead “Judas shall be glad of substitution and love it, […] His exclusion shall become his inclusion”. But, uniquely, in Williams’s last play, The House of the Octopus (1945), characters are killed in the course of the story and immediately rejoin the action. The first is Alayu, an island village’s youngest convert, who apostatizes from fear, and is struck dead in response to her clutching an invading soldier in her pleading. She soon returns, saying, “Just as I died, / I knew it was true,” and that she “was sent to ask” forgiveness. She is then further called on to bear the fear of her father in Christ, the missionary priest, Anthony. He had both condemned her apostasy and is himself willing to equivocate with Christianity and the invaders’ totalitarian ideology in his own fear of death. When he seems shocked to see and speak with her, “one of the dead”, she replies, “but you said / we were dead in Christ; there is nothing new in being dead.” The other converts agree. One speaks for all to the threatening Prefect: “We have been dead a long while”. They rejoice that martyrdom will seal their dying in Christ which replaced their earlier being dead in sin. After which, they are machine-gunned in numbers, to be raised again to close the play singing a hymn to the Holy Spirit.

Perhaps what (pardon the expression) most haunts these works, is how Williams pictures a character who is physically neither ‘dead’ nor ‘asleep in the Lord’, Wentworth, to whose life the title Descent into Hell seems clearly to apply. In Williams’s mind, has Wentworth lulled his conscience asleep and descended so far into the incoherence of self-worship in the time of this mortal life, that he can never be delivered from the sting of such spiritual death? In any case, I can imagine Williams, working on All Hallows’ Eve in the spring of 1944, enjoying hearing Lewis at an Inklings session reading from his own work in progress, finally published as The Great Divorce. In Lewis’s dream-vision, the character George MacDonald says, “Only One has descended into Hell. […] All moments that have been or shall be were, or are, present in the moment of His descending. There is no spirit in prison to whom He did not preach.”

Wow! I love this review. It firms up exactly why CW is so intriguing to me, affirming, if you will. He did appear to ‘know things’ as CSL said of him. That true wisdom consists in non-dual thinking. Dead and not dead at the same time! That things can be true on one level and not true on another. One is reminded of Jesus, human and divine at the same time, the classic non-dual thinker who deals creatively with mystery. CW’s novel leads us to the mystery that we cannot love or forgive, or even be patient if we are totally dualistic.

LikeLike

Thanks! (“Dead and not dead at the same time” reminds me that, until I read it in Michael Ward’s Planet Narnia, I had not realized Schrödinger and Lewis were Fellows of Magdalen at the same time – in fact, around the time Lewis and Williams got acquainted, but before Williams came to Oxford: it was in fact during this time that Schrödinger imagined his famous “iving and dead cat (pardon the expression) mixed or smeared out in equal parts.”)

LikeLike

My apologies: “living and dead cat”!

LikeLike

I’m sorry – but I cannot accept that that is a photo of David Llewellyn Dodds – I feel as if I know him well from his many comments here and on my blog, and he does not have a beard nor does he wear a T-shirt.

I can picture him perfectly: He is about 75 years old with white hair, clean shaven, wears a tweed jacket with leather patches on the elbows, and smokes a pipe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sic et non, professor! My hair is whiter (or at least more silvery) now, than in that photo (from my Place of the Lion guest post: hence the Angel-ikons book!*), I do smoke a pipe, and wear tweed jackets (though only my corduroy one has elbow patches), I used to alternate being clean-shaven and bearded with summer and winter, but have rather settled into the insouciance of an even bushier sort of barbe de complaisance year-round, lately, and am only in my sixtieth year.

*Note, however, the suitability of the Mythcon 32 T-shirt to the current post: “I see dead Inklings” (though I have still not caught up with M. Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense: I was tempted, this Hallowe’en in Oxford when some channel was going to broadcast it around midnight, but thought sleep more judicious with an eye to Sunday morning service time).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve somehow missed knowing about Lucy M. Boston’s Green Knowe series (illustrated by her son, Peter) until buying a second-hand copy of The Chimneys of Green Knowe (1958: U.S. title, Treasure of Green Knowe) when in Oxford for Grevel’s biography launch, and I have now read it with considerable enjoyment. It’s the second of the series, and I’m attempting to avoid receiving as well as giving spoilers, but I will say generally, that in a way, something like Pauline’s encounter with John Struther is thematic for the whole book (and, apparently, the whole series), in a much lower-key way – even when someone from the Twentieth century daringly helps someone from the turn of the Eighteen-Nineteenth centuries, in The Chimneys.

It brings home to me how little I know of this sort of time-interaction story(-element). For example, where do Kipling’s Puck books come in, here? How much conscious literary borrowing or tradition is likely to be involved? Is it something different writers tend to ‘re-invent’ in whatever degree? (E.g., what of Alan Garner’s Red Shift?)

Reading John Matthews’s Song of Taliesin in parallel with it has got me thinking anew about the extraordinary, mysterious poetry attributed to Taliesin with its astonishing range of different time-presence and -activity claims. For instance, how far does the action of Williams’s “Mount Badon” effectively fit in with this poetry, inventing a new instance? And how far may Williams’s most extensive and minutely source-related use of it in “The Calling of Taliessin” be directly indebted to his having read David Jones’s use in In Parenthesis, which he knew in proof? Again, might it in any way contribute to the mental time-travel aspects of Tolkien’s Notion Club Papers?

LikeLike

We know from his Arthurian Commonplace Book that Williams knew a novel which could be viewed as a sort of precursor of his own, Robert Hugh Benson’s The Necromancers (1909), which is concerned with spiritualism – and its dangers. (It’s scanned in the Internet Archive and transcribed at Project Gutenberg.) But I’ve just learnt that there was a film based on it, released in the UK on 10 May 1941 (according to the IMDB), which bears quite an assortment of titles: Spellbound (in the UK, but reissued there as Passing Clouds), and The Spell of Amy Nugent (in the US, where it only came out in 1945), and, on television, simply Ghost Story.

I just encountered it as Ghost Story, with an indication of its source in the title under which it is posted, on YouTube – and note that fact, before watching it myself!

But, it occurs to me to wonder if it might give an idea of what it could have been like if one of Williams’s novels had been adapted for the movies in his lifetime.

And, I wonder if Williams might have seen it, while working on the first version of his last novel (chapters of which were published in Mythlore as “The Noises That Weren’t There”).

It will also be interesting to see if it, like its source, has elements comparable to some in Lewis’s Perelandra (and, in a way, in That Hideous Strength, as well).

(It’s worth noting IMDB misidentifies the author of its source, linking a different ‘Hugh Benson’.)

LikeLike

Brenton Dickieson’s recent post, “Is Saint Denys in the Headless Hunt? Martyr Legends and Nearly Headless Nick’s Fate”, has got me thinking about how many different characters in Williams novels invite comparison (and contrast) with Nearly Headless Nick in not (yet) having “gone on” (Order of the Phoenix, ch. 38) – and how little I know about this as topos or in lore (beyond a passage in Milton’s Comus which springs to mind):

LikeLike

Just encountered this, which, among other food for thought, includes “This, for Williams, is hell: the self unmitigated by otherness (to borrow from Martin Buber).” I wonder if Jane Clark Scharl has written more about Williams that I have not encountered? :

https://www.crisismagazine.com/2018/the-end-of-identity-charles-williams-sex-robots-and-hell

LikeLike