What books stir your soul?

Which time period of literature or art appeals to you the most? Which stylistic era of music most stirs your soul? Is it the ordered precision of a Bach fugue or the poignant strains of a Chopin prelude? Alexander Pope’s witty epigrams or Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s sublime musicality? The powerful catharsis of a tragedy by Sophocles or the messy psychological accuracy of one by Shakespeare?

Which time period of literature or art appeals to you the most? Which stylistic era of music most stirs your soul? Is it the ordered precision of a Bach fugue or the poignant strains of a Chopin prelude? Alexander Pope’s witty epigrams or Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s sublime musicality? The powerful catharsis of a tragedy by Sophocles or the messy psychological accuracy of one by Shakespeare?

C.S. Lewis, in describing the literary taste of his parents, wrote: “Neither had ever listened for the horns of elfland” (Surprised by Joy 5).

The Heraldry of Heaven

The horns of elfland, the blue flower, sweet desire, divine discontent, the heraldry of heaven, Sehnsucht, Joy…. These are all names for a kind of painful yearning or beautiful longing that Lewis felt many times throughout this life, usually stirred by “Romantic” poetry, fiction, or music—or by nature. I gave a talk about this particular kind of Joy last week at Mythgard; you can listen to, watch, or download the talk here.

The horns of elfland, the blue flower, sweet desire, divine discontent, the heraldry of heaven, Sehnsucht, Joy…. These are all names for a kind of painful yearning or beautiful longing that Lewis felt many times throughout this life, usually stirred by “Romantic” poetry, fiction, or music—or by nature. I gave a talk about this particular kind of Joy last week at Mythgard; you can listen to, watch, or download the talk here.

The Romantic Note

The point I want to make right now is that it wasn’t just all good literature that gave Lewis this strange longing; it was only works with those that have a “Romantic” tone to them, from whatever time period. Chopin would do it for him while Bach wouldn’t, even though Bach’s music might raise the soul to heights of glory and flights of heavenward delight. Bach’s music doesn’t have that sense of incompletion, of fragmentary suggestion, of hints and intimations of immortality. Bach’s music often seems to contain the very eternity of which is speaks, whereas Chopin’s gestures towards the sublime in a way that evokes our yearning for it but does not fulfill the yearning—which thus feeds the longing all the more.

External and Internal

This distinction may be related to the evolution of the “expressive theory of art” as defined by M.H. Abrams in The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition. Bach may be categorized as expressing in his compositions something outside of him: a kind of symmetry and order he observed in the universe, while Chopin might be characterized as expressing feelings evoked in himself (and thus in his listeners) about what he saw in nature.

Complete and Incomplete

This brings me back to the idea of completion and incompletion: Bach’s compositions have a satisfying sense of achievement about them: they are finished in two senses, both polished and complete. Chopin’s have a sense of suggestion, of being only a fragment of so much more. Perhaps I am overstating the case here, and I would love to have composers, music theorists, musicians, and music teachers argue with me here. Let me turn to literary examples. The Canterbury Tales, for all its stated fragmentary nature, does not arouse in its reader that longing for some spiritual beauty beyond itself. It contains all its satisfaction inside itself: its jokes, insults, ideas, and speculations are all self-contained. You put down the book feeling satisfied. You’ve had your meal. But that same author’s Troilus and Criseyde, even though it is a complete work, evokes much more spiritual longing and sense of something more, I think, in its hints and suggestions about heaven, Troilus’s soul, and so forth.

In other words, Troilus and Criseyde could evoke Sehnsucht in readers, while The Canterbury Tales is highly unlikely to do so.

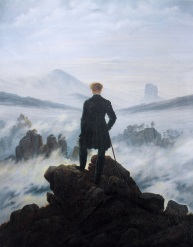

Lewis loved any work that could provoke this longing, and he strove to evoke it in his own readers, too. J.R.R. Tolkien also packed his writings with longing, with the romantic note, with a wild, sweet, painful yearning for something located off in the west, beyond the seas, beyond the world, that is inaccessible and infinitely desirable. The sound of the sea stirs the heart in both of these writers. Long landscapes, distant vistas, shrouded in mist and tinted by twilight, also awaken desire. Autumn, western winds, the cries of geese or gulls, mountain ranges fading off into fog, the distant past paradise or the unattainable future heaven—these are lavished throughout the works of Lewis and Tolkien.

Lewis loved any work that could provoke this longing, and he strove to evoke it in his own readers, too. J.R.R. Tolkien also packed his writings with longing, with the romantic note, with a wild, sweet, painful yearning for something located off in the west, beyond the seas, beyond the world, that is inaccessible and infinitely desirable. The sound of the sea stirs the heart in both of these writers. Long landscapes, distant vistas, shrouded in mist and tinted by twilight, also awaken desire. Autumn, western winds, the cries of geese or gulls, mountain ranges fading off into fog, the distant past paradise or the unattainable future heaven—these are lavished throughout the works of Lewis and Tolkien.

What about Williams?

And what about Charles Williams? Do his works stir up Sehnsucht in the soul of the reader?

I don’t think they do. His books, especially his novels, do fill me with desire, but it is an entirely different desire: It is the longing for holiness. It is the aspiration to become a saint or a mystic. This is worlds away from the autumnal, Hesperian wanderlust aroused by a recitation of “Kubla Khan.” And there are also passages in CW’s writings that raise the heart to heavenly heights, filled with the golden glory of God’s presence or the profound peace of a soul’s submission—but this is in Bach’s category of sublimity, not Chopin’s.

How about for you? Are there any passages in CW’s work that strike you the way this one from Tolkien does?

And it is said by the Eldar that in water there lives yet the echo of the Music of the Ainur more than in any substance else that is in this Earth; and many of the Children of Ilúvatar hearken still unsated to the voices of the Sea, and yet know not for what they listen (Silmarillion 8).

Or the way this one from Lewis does?

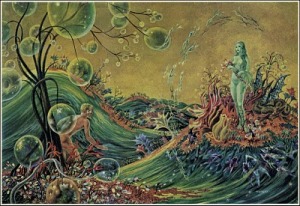

The sky was pure, flat gold like the background of a medieval picture….The water gleamed, the sky burned with gold, but all was rich and dim, and his eyes fed upon it undazzled and unaching. The very names of green and gold, which he used perforce in describing the scene, are too harsh for the tenderness, the muted iridescence, of that warm, maternal, delicately gorgeous world. It was mild to look upon as evening, warm like summer noon, gentle and winning like early dawn. It was altogether pleasurable. He sighed. (Perelandra 36).

Is there anything like that in Williams for you? I can’t think of any moments. There is plenty of beauty, but it’s of the more “Classical” kind, isn’t it?

And I think I know the reason. CW didn’t like nature. He was a city man at heart. He did like long walks, but his sight wasn’t very good, so he couldn’t enjoy long vistas of mountains and mist the way CSL and JRRT did. He much preferred to be in the heart of London, among the busses and traffic and crowds of coinherent humans. CSL and JRRT despised cars, trains, pollution, noise, hustle, and bustle. Williams loved all of that. So perhaps that’s why the note or tone of their works is so wildly different.

Or perhaps I’m wrong. Go ahead and prove me wrong. Is there a passage in CW’s works where you hear the horns of elfland?

Sørina,

I’m not yet well versed enough in Williams to comment on him, but On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer has always both inspired and in a way summarized that longing for me. Whenever I find myself feeling that longing because of something I have read, or heard, or because I am standing beside the sea, Keats’ words come to me:

“Or like stout Cortez, when with eagle eyes

He stared at the Pacific—and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.”

So many vistas open in this poem, one after the other.

The longing also sometimes comes to me when I listen to Bach, especially the adagio of his Concerto in C minor for oboe and violin (BWV 1060).

Thanks for the thoughtful post.

tom hillman

LikeLike

Thank you for this comment, Tom! It’s very beautifully written. That Keats poem is wonderful. And it’s funny that you get the feeling with Bach!

LikeLike

I read the Keats sonnet the year I read LOTR and I always mentally titled it ‘On First Looking Into Tolkien ‘ s Ring’.

LikeLike

That’s so cool!!

LikeLike

Wonderful post – I think your Canterbury/Troilus contrast was the most compelling illustration for me, and put things in perspective, but your observation about a love of nature also seems apt. The latter is why I prefer Plato’s Phaedrus to nearly any other dialogue – it’s the only one that takes up the mystery, madness, and dynamis of nature.

LikeLike

Oo, good point. I haven’t read that dialogue in a very long time! Thanks for the reminder.

LikeLike

I remember a Sunday evening as a small boy when my mother, who was very strict about the hour of bed time throughout my childhood, announced that the time had come for me to go upstairs. As I stood up to go an orchestra began to play on our small black and white TV and I was suddenly transfixed by the beauty of what they were playing. I could hear my mother telling me to do as she had told me but there was an even stronger voice coming from the TV that was even more compelling. I do not know what the orchestra were playing although I have made a guess at it (it was not Bach!) but I don’t think that this matters. The words you quoted from Tolkien evoke that experience well, “and many of the Children of Ilúvatar hearken still unsated to the voices of the Sea, and yet know not for what they listen”. It would not be the particular notes that were played that evening that would satisfy my still unsated desire, I know that they point to an Unknowing, perhaps The Unknowing that as the author of “The Cloud of Unknowing” said, cannot be grasped and held by knowing but only by love.

On CW and London, I am not sure that it was a distinction between the city and the country that holds the key to understanding his temperament. I had to pull over to the side of the road once while listening to Vaughan Williams’ London Symphony because the tears I was shedding made me a dangerous driver for a time and I know that VW was a great lover of that city and much of his music is an expression of the longing you so beautifully describe. I also once had a profound spiritual experience overlooking the rooftops of Islington which really were not beautiful no matter what Bert sings of in “Chim Chimeny” in the wonderful Mary Poppins! I also have to cite William Blake who rarely ventured beyond London in his life and yet was, of course, a truly great visionary. All I know of myself is that I would rather have my longing than someone else’s certainty.

LikeLike

That’s a beautiful, beautiful story. Thank you very much for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Re Stephen’s comment about rooftops in Islington, I always count the passage in All Hallow’s Eve where Jonathan’s painting of London is described as one of the most genuinely mystical in CW’s oeuvre. I love that bit about the light coming from ‘within the painting itself.’ I wonder if CW had lived whether his writing would have taken on more of this almost Jacob Boehme-like sensitivity to the depths and ‘inner light’ of people, places, things, etc. Great piece Sorina.

LikeLike

Excellent points, Stephen and John. I did think of that passage about the painting! Is it the same longing, though, as CSL’s very specific yearning? I wonder.

LikeLike

To blurt out something that springs to mind, and I haven’t checked, yet: I am reminded of Roger’s thoughts in Shadows of Ecstasy about Ariel and his song ‘Where the bee sucks’ in Shakespeare’s Tempest. Has Roger had/is he having such a ‘Sehnsucht’ experience? Are we invited to enter into it? If so, is Williams doing it ‘critically’ in a certain sense, by way of Shakespeare? (Time to re-read!)

LikeLike

Is this the passage?

“It was a large high room, and there moved in it continually a little tender breeze, as of spring, though there were no windows, or, if there were, they were hidden behind the pale yellow hangings which here also hid the walls. They shook, ever so faintly, in the movement of the air, and it seemed to Roger for a few moments as if everywhere great fields of daffodils trembled in that gentle wind. The vague suggestion passed, and left in its stead a thought of a universal sun shedding a golden presence through clear air, and then that again vanished, and he knew they were only wonderfully wrought hangings, and some beautiful light diffused itself over them.”

If so, it does sound very like CSL’s sensibility!

LikeLike

I think there are passages in Williams of the quality you describe, but they are mostly in the poems. What about:

everywhere the light through the great leaves is blown

on your substantial flesh, and everywhere your glory frames.

‘Bors to Elayne: The Fish of Broceliande’, 47-8

Proportion of circle to diameter, and the near asymptote

Blanchefleur’s smile; there in the throat her greeting

sprang, and sang in the one note the infinite decimal.

‘The Sister of Percivale’, 61-3

In this second example you feel at the end the infinity which is the expansion of pi. I also think that in the novels All Hallows Eve is suffused with this quality. Jonathan’s painting of London, incidentally, always seem to me as if it were based on one of John Piper’s wartime pictures. Williams might have seen one or, I guess, someone described one to him and he remembered the description and drew on it.

LikeLike

These are definitely lofty moments, perhaps infused with a sense of the Sublime, but I don’t feel that yearning infinity of CSL’s Sehnsucht.

LikeLike

I am getting convinced I need to reread All Hallows’ Eve, with an eye to this very interesting question! I had been wondering about the end of the book (as I remember it), in this respect. Now (I’ll say mysteriously, to avoid spoilers) I am also wondering if Lester’s homunculus experience does not provide a very original, extraordinary, evocative presentation of ‘Sehnsucht’!

LikeLike

Oh, I don’t think so! I don’t think so at all!!

LikeLike

CBS sense of the otherworldly seems closest to that of the Symbolists. Dante ‘ s place in his imagination is perhaps decisive in the elimination of the horns of Elfland, which belong to the Northernness CSL and JRRT. Tolkien of course couldn’t abide Dante.

LikeLike

I find the subject of Tolkien and Dante an intriguing one, not least because Letter 294 is, I think, the only definite, explicit thing I know. A first foray online turned up Jacopo della Quercia’s little paper of last year, including its footnotes:

http://www.princeton.edu/~dante/ebdsa/quercia121113.html

Also intriguing in this context are Toklien’s remarks in Letter 71, with reference to Lord of the Rings, that ” ‘romance’ has grown out ‘allegory’, and its wars are still derived from the ‘inner war’ of allegory”.

Where do the ‘figures’ of Dante, the ‘figures’ of Williams’s poetry, and the characters of Williams’s and Tolkien’s prose ‘romances’ fit in, against stricter ‘allegorical’ background, and how compatible are ‘Commedia’, allegory, and whatever Williams writes, with occasions for ‘Sehnsucht’?

LikeLike

Tolkien so effectively cloaked his deeper intentions that I meet many contemporary readers who think that the Tolkien was pagan; and I have to point them towards the Letters and To Morgoth’s Ring. (It’s also suggestive that so many readers don’t know how to approach his creation story.) Tolkien ‘ s ur-theological method -ur-philosophical as well? – introduces as many twists to the question as Williams esoteric Anglican – plotinian reading of Dante does. Tolkien ‘ s figures haven’t yet advanced to the figural state at all – they are the other side of allegory from us; They point forward towards the figures that we will recognize in later imagination, and are all the more themselves. Dante ‘ s figures are equal part person and figure – whereas in Williams the person subsumed within figure & pattern.

LikeLike

Thank you for such a response!

There was a little national newspaper discussion earlier this year (unfortunately for convenient reading, in Dutch), where one contributor told how Tolkien’s works about Middle-earth had led him to become a Christian, and yet thought the mythology in them was deliberately pagan.

But have you written in more detail about Tolkien along the lines you sketch here? – it could not but make rewarding reading, if so!

One thing that strikes me strongly about Tolkien’s Middle-earth is typology. Another thought I have had, is to wonder how much he is playing with constructing ur-histories (of one sort or another) behind later myths and legends: e.g, the Children of Hurin and perhaps both the Nibelungen material and Kullervo.

(It strikes me that Williams might be doing something analogous with the Angelicals in The Place of the Lion, and, indeed, with the Arthurian material. And what might this have to do with Waite’s life-long attention to ‘secret tradition’…?)

LikeLike

It’s been some 30 years since I’ve written on these things; I departed academe at the dawn of PC when the bureaucratic bulldozers were droning straight at the edifice of Western literature. Rereading ‘That Hideous Strength’ sent me back to CW.

LikeLike

In Lewis I got that feeling when Reepicheep sets out for the land beyond the East, in Tolkien at the Grey Havens. In the music of Mozart (especially his 39th symphony). In Williams, no. Perhaps the nearest he gets to it is when Richardson takes off in “The place of the lion”.

LikeLike

Steve: Yes to Reepicheep and the Grey Havens! But really, when Richardson commits suicide? Whew, that’s a rough bit.

LikeLike

I’m not sure that Richardson’s end was suicide. I suspect that his end was like that of Enoch, and Moses, and Elijah. The first time I read the book, I got the impression that he sprang on the unicorn as it was passing, and rode away on it, On rereading it, I saw that he didn’t, at least not before the eyes of Anthony Durrant, but no one saw him, or what became of him.

LikeLike

I know we had a debate on here once before about whether Richardson’s end was suicide, but now I can’t find it any more… I believe it was, and therefore the narrator’s strong approbation of it disturbs me.

LikeLike