Here is Post #7 in the Series on Taliessin through Logres! Please visit the INTRODUCTION to this series first, and here is the INDEX to the other posts in the series.

Here is Post #7 in the Series on Taliessin through Logres! Please visit the INTRODUCTION to this series first, and here is the INDEX to the other posts in the series.

Today’s post is by Jenn Raimundo.

Jennifer Raimundo has been an Inklings enthusiast for the better part of her life. After realising that there will always be more to learn about this merry band of brothers, she began her formal education in Inklings and Classical Studies through an M.A. in Language and Literature at Signum University. In addition to being a student, she serves as Institutional Planning Lead at the University. While not doing work or school, Jenn is probably traipsing around the world, drinking coffee and listening to music and learning to love God more like how He loves her.

Jennifer Raimundo has been an Inklings enthusiast for the better part of her life. After realising that there will always be more to learn about this merry band of brothers, she began her formal education in Inklings and Classical Studies through an M.A. in Language and Literature at Signum University. In addition to being a student, she serves as Institutional Planning Lead at the University. While not doing work or school, Jenn is probably traipsing around the world, drinking coffee and listening to music and learning to love God more like how He loves her.

VII. ‘Crystal in Crimson’: Gospel Paradox in ‘Taliessin’s Song of the Unicorn’

What do the crucifixion, woodland sex, classical unities, church tradition, mythical beasts, an original geography of medieval legend, and evangelistic hope have to do with each other? A Charles Williams poem, of course.

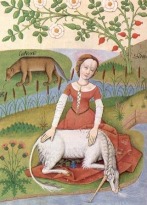

The storyline of ‘Taliessin’s Song of the Unicorn’ is quite simple, which is a mercy because nothing else about the poem is. A magnificent albeit non-communicative mythical shape (the titular unicorn) leaves his world and enters into a space where most women will be entirely chilled by his advances. But one very special sort of woman will be thrust to the heart by the unicorn’s horn and thereby become the mother to this heretofore inaudible creature’s Voice.

The storyline of ‘Taliessin’s Song of the Unicorn’ is quite simple, which is a mercy because nothing else about the poem is. A magnificent albeit non-communicative mythical shape (the titular unicorn) leaves his world and enters into a space where most women will be entirely chilled by his advances. But one very special sort of woman will be thrust to the heart by the unicorn’s horn and thereby become the mother to this heretofore inaudible creature’s Voice.

It’s all very poetic, granted. But what is the point?

The answer to that question merits digital reams of blog posts (another series, Sørina?), but one aspect of ‘Taliessin’s Song of the Unicorn’ draws my attention.

The poem bursts with paradox.

It opens with Broceliande’s heavenly ‘shouldering shapes’ but quickly contrasts them with Caucasia’s ‘rumours in the flesh.’ It describes the unicorn as the best beast for verse, but then asserts that the unicorn has no voice. We learn that lusty women will experience the unicorn’s horn as a ‘ghostly threat,’ but that a virgin (for according to legend a virgin alone can tame the ‘quick panting’ unicorn) who is willing to suffer will feel its ‘thrust to stun her arteries.’ And just when we find ourselves stuck in a steamy sex scene, we suddenly realise that Williams has been talking about Christ’s cross this entire time. The thrust causes this woman’s arteries to flow ‘crimson in crystal,’ the ‘twy-fount’ water and blood of Golgotha’s hill.

It opens with Broceliande’s heavenly ‘shouldering shapes’ but quickly contrasts them with Caucasia’s ‘rumours in the flesh.’ It describes the unicorn as the best beast for verse, but then asserts that the unicorn has no voice. We learn that lusty women will experience the unicorn’s horn as a ‘ghostly threat,’ but that a virgin (for according to legend a virgin alone can tame the ‘quick panting’ unicorn) who is willing to suffer will feel its ‘thrust to stun her arteries.’ And just when we find ourselves stuck in a steamy sex scene, we suddenly realise that Williams has been talking about Christ’s cross this entire time. The thrust causes this woman’s arteries to flow ‘crimson in crystal,’ the ‘twy-fount’ water and blood of Golgotha’s hill.

The paradox continues, for it is not from the unicorn that the gushing flows; it is from the woman. It is she, not the unicorn, who is pinned against the ‘dark bark’ of the ‘one giant tree’ behind her. It is her heart that is plied open by the unicorn’s longing. It is she who is nailed to the cross. And once the pinning and plying of the act of love is done, this woman is praised as translucent and virtuous, lit by her throes. She is now a mother, the Mother of the Unicorn’s Voice, and this makes her awesome in the eyes of men. Thus her sensuous experience ends in purity and praise. Her ‘intellectual nuptials’ have unclosed the gift of a new song to the world of flesh.

It’s brilliant. Through Taliessin’s voice, Williams uses a gentle chiasmus to join earth and heaven, science and myth, pain and pleasure, sensuality and chastity, life and death—at the cross.

The poem opens with a predicament: shouldering shapes in the sky of Broceliande have no voice to relate to the fleshly inhabitants of Caucasia. In Williams’s mythological geography, Broceliande is the land far to the west that is the beginning of all things, the place of creative vision and genitive idea. On the other hand, Caucasia is a region in the east that is marked by sensuality, the flesh, and a total disaffection to all things sublime. The Caucasian maid cannot respond to the unicorn. After their meeting at the dark bark, however, we find a one-to-one response to this problem. The ethereal shape reaches the body, the hands and heart, of a woman. The first divide crossed, a Song is born that tells the world of the abstract realities and mythic beauties of Broceliande. From Caucasia to Logres, the world now has a chance to hear the unicorn’s voice. A sumptuous balance comes to life at the tree, and now the whole world can hear its truth.

The woman’s personal tension, too, is resolved. At the heart of the text, Williams marries the image of a truant love-act with that of a true man setting a maiden free. This image then bleeds into the death and exaltation of the Voice’s Mother. There the cleansing crystal of Broceliande and the corporeal crimson of Caucasia course together in her veins. This woman’s relationship with the unicorn is her redemption. Before she was just a cunning maid west of Caucasia, but now she is pure and reproductive, the mother of the Voice that will sing a song of organic and divine hope to the world.

This new life all happened at the death on the tree. That is the paradox I cannot escape, and I think it is the paradox that Williams loved the most. Lovers give themselves to each other to make life. Poets give themselves to their subject to create a unified song. The unicorn’s longing at once kills and resurrects the woman to purity and fruit. Christ brings His Bride to the cross and gives her a new life to share with the world.

This new life all happened at the death on the tree. That is the paradox I cannot escape, and I think it is the paradox that Williams loved the most. Lovers give themselves to each other to make life. Poets give themselves to their subject to create a unified song. The unicorn’s longing at once kills and resurrects the woman to purity and fruit. Christ brings His Bride to the cross and gives her a new life to share with the world.

In ‘Taliessin’s Song of the Unicorn,’ Williams ties all these pictures together in a way that makes readers stop and think, and once they see connections, they will never forget the point. Still, the connectivity of the imagery gets tangled rather quickly. Is the poem about the sylvan scene of a spoiled maidenhead, the regeneration that happens by Christ’s transformative work on the cross, or the ‘intellectual nuptials’ between fleshly rumours and abstract science, story and mathematics? The answer is probably all of the above, and from what I’ve learned about Williams so far, he would have argued that you cannot have any one of the meanings apart from the other two. For him, forest cuckoldry, the spiritual marriage that begets the feeling intellect, and the believer’s death and resurrection with Christ are inseparable. Unfortunately, his life shows just how far he took these connections. But, under the mercy, his sins won’t stop me from remembering this paradox: you have to die to live, and the best death meets the best life at the cross. That gives us something to sing about.

very nicely done; excellent writeup of a very moving poem.

LikeLike

Thank you! I am glad you enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Wow! You’ve given us a lot to think about, here! Thank you!

LikeLike

Oh, good! Reading this poem particularly was a mind explosion. And there is so much more material in it yet to be discussed!

LikeLike

You’ve got me wondering about all sorts of comparisons and connections – like Barbara Rackstraw in his novel, War in Heaven, and the fact that he wrote an English translation of the Stabat Mater Dolorosa for a musical setting, published in 1926…

Thanks again!

LikeLike

YES: the Barbara Jackstraw connection is definitely one to be explored. Care to share some of your thoughts?

Ohhh, I had no idea he did that translation! Is it available to the general public? I shall have to look into this.

LikeLike

Ugh. *Rackstraw* That’s what I get for not editing before posting. 🙂

LikeLike

I’d have to look up the exact reference, but Barbara Rackstraw is leaning against a fence with her arms outstretched and looks like she’s crucified.

The Stabat Mater was published commercially, so copies are probably ‘out there’ in all sorts of places. One known place is the Williams Society Archive in Oxford, as the online catalogue lists “Two copies of the text and music of Stabat Mater Dolorosa, by George Oldroyd, English translation by CW, pub. OUP, 1926, 34 pages.

“One with no cover, but the other a gift to the CW Soc. on 17 Oct 1977 by Ralph Binfield , note included.”

And I see that the Wade online list of Williams manuscripts lists a typescript copy of the text under CW / MS-29 / X.

LikeLike

Ah, yes! I’m very interested in this servant girl throughout the poem collection, and Rackstraw comparison is only feeding my very strange theories about her. Thanks!

And thank you for the Stabat Mater details. Very helpful.

LikeLike

One of the exciting things about your post is getting ‘us’ (me, certainly) to think about whom this poem might be addressed to – or who might respond to it, once it exists – like the girl hearing Taliessin sing to Percivale’s harping, in a later poem in the book. Different knights and ‘ladies’ have each their unique ‘courtly lovers’, and Taliessin and Blanchefleur will be – much (anyway) – like this, and yet… That’s not the whole story with Taliessin in these poems. (And that is something new – not in Williams’s earliest plans, so far as I can see, nor in the ‘Advent of Galahad’ poetry from the late 1920s – early 1930s: and you’re getting us to think about this, in a new way! So, thanks again!)

LikeLike

Do you mean Taliessin’s relationship with the servant girl v. Blanchefleur? If so…my next post will touch on that subject rather wildly. You can always leave your thoughts here for me to steal them! 😛

LikeLike

Yes. There is some attention to the ‘common folk’ of Logres in the Advent of Galahad poetry (included Gareth similarly working at lowliest tasks), where Taliessin’s beloved is the Byzantine Princess, Caelia, who has died, but there is no specific attention to late-antique/early mediaeval Christian slavery, and certainly no slave girls singled out for poetic attention. And at that stage (as far as I can see), Williams was treating Blanchefleur not as Percivale’s actual sister, but as a ‘sister’ in the sense of chaste beloved: like the lover and beloved in Williams’s first book, The Silver Stair. Whereas (so far as I can see), in Taliessin through Logres, Williams goes back to the sources which have Percivale, Lamorack, and Blanchefleur as actual siblings. So, the 1938 Percivale does not clearly have a ‘beloved’, and Taliessin and Blanchefleur in some ways correspond to the earlier Percivale-Blanchefleur(-as-beloved) pair. There are obvious differences, too. There is no later Taliessin poem to Blanchefleur corresponding to the Percivale- Blanchefleur one published in Heroes & Kings (1931), for instance.

This Song of the Unicorn started as a pair of not obviously Arthurian sonnets to Phyllis Jones, which were deftly ‘Arhturianized’/’Taliessinized’. And in Williams’s Century of poems to her (some of which are quoted in print, or published, especially in Gavin Ashenden’s study and in The Masques of Amen House edition), he develops a sort of tripartite imagery for Jones of which the upper extreme is ‘Celia’ and the lower, ‘Circassia’. As Williams moved from the Advent poetry to what would become the Taliessin through Logres poetry (notably, the Prelude in its various versions) ‘Circassia’ is introduced into the geography and geographical imagery, where this 1938 book has ‘Caucasia’.

I don’t know how finely Williams had worked out when Blanchefleur decided to answer a calling to be a nun, and under what circumstances, and with what story-background, by the time Taliessin through Logres was published. (If ‘we’ know, I don’t know it by heart!) So, it seems to me conceivable that there could be a deliberate ‘Blanchefleur-dimension’ to this Song of the Unicorn, if we take it to be written/sung before she responded to a calling to the conventual life.

LikeLike

I wonder if Williams’s knew the ‘Stabat Mater speciosa’ as well? (He could have – from the ‘Stabat Mater’ article in the Catholic Encyclopedia (1912), for example.) I can imagine him enjoying the two, together, if he did.

LikeLike

Ah, the delicious world of speculation.

LikeLike