I’m having two problems in my Charles-Williams-related life right now.

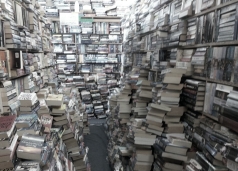

The first is the inaccessibility of his books. I’m not teaching at a local campus these days—only at Signum University online, where I recently took on the role of Chair of the Department of Language and Literature, so I’ve got plenty to do—which means that I do not have a college or university library system I can use. I was keeping the Interlibrary loan department busy with my odd requests regularly when I was teaching at the local state school and/or community college, but I can’t expect my little tiny public library to do that all the time. Here’s a recent phone conversation I had with a librarian at my little local library:

The first is the inaccessibility of his books. I’m not teaching at a local campus these days—only at Signum University online, where I recently took on the role of Chair of the Department of Language and Literature, so I’ve got plenty to do—which means that I do not have a college or university library system I can use. I was keeping the Interlibrary loan department busy with my odd requests regularly when I was teaching at the local state school and/or community college, but I can’t expect my little tiny public library to do that all the time. Here’s a recent phone conversation I had with a librarian at my little local library:

Me: Hello. I’m wondering if I can submit an interlibrary loan request online.

Librarian: Yes, you can.

Me: Okay, excellent. I’m on the book’s catalog page, and I can’t see where to do it.

Librarian: I’ll talk you through it.

<gives about 20 steps, ending on the book’s catalog page>.

There you go.

Me: But… that’s where I was when we started. I still don’t see how to submit the request online.

Librarian: You have to print the page out and bring it to the library.

Me: But… you said I could do it online.

Librarian: Oh! You wanted to do it *online*?

I’m not dissing my public library; they’re adorable and usually super helpful. But they’re not used to getting requests for out-of-print books by obscure dead British authors.

I’m not dissing my public library; they’re adorable and usually super helpful. But they’re not used to getting requests for out-of-print books by obscure dead British authors.

The other solution is to use WorldCat to find a copy in a college or university library near me, sneak in, and spend a day reading the book there without checking it out. That’s what I’ve been doing a lot recently. (Don’t tell). But the ones I need to read these days aren’t anywhere near me: CW’s bio of Rochester, for instance, isn’t in any libraries within an hour drive of here. I could buy it on amazon, but I really don’t want it; I hope I never have to read his biographies more than once.

And then there are others that have never even been published, but are held in manuscript in either the Wade or the Bodleian, and I certainly can’t afford the time or the money to travel there again right now.

Therefore, I’m having to skip several of his works in my chronological blog-through. Here are the ones we are missing so far:

- Prince Rudolph of Silvania (1902, drama, in the Wade)

- Scene from a Mystery (1919, a play, I think?)

- Bethnal Green Pageant (1935, a play, in the Wade)

- Rochester (1935, a biography)

- Queen Elizabeth (1936, biography)

- Henry VII (1937, biography)

- Stories of Great Names (1937, biography)

So here is my question: Do YOU have access to any of these books? Would YOU be willing to write up a 1000-word summary like the ones I’ve been posting for the others? Please say Yes! You will be my hero!

Now on to my second complaint about Charles Williams. He’s really starting to annoy me. I shouldn’t confess that, I know. I am dedicated to getting others to read his works, to blogging my way through, to annotating his poetry (someday). But not all of his works are super great. There’s definitely a hierarchy. And even his best works feel unfinished, unpolished, inaccessible. Here’s a conversation I had recently at MidMoot with The Tolkien Professor:

Corey Olsen, talking about the house he and his wife bought recently: “We kept telling the real estate agent, ‘We don’t want “potential.” We want “actuality.”’”

Me, later, talking about getting sick of Charles Williams: “Charles Williams has a lot of potential. It would be refreshing to work on a poet with actuality.”

Corey: “So, Charles Williams is a bit of a fixer-upper?”

That’s exactly it. I want to grab my purple pen and fix up his works. If I could just re-arrange his syntax, substitute clear words for needlessly obscure ones, and cut some of the more impossible phrases, his works would be so much nicer. Maybe we could actually understand them.

It’s frustrating: I’ve spent a good chunk of the last 6 years reading his stuff, studying it, analyzing it, writing about it, transcribing it, editing it, publishing it—you’d think *I* of all people could understand it by now. And I do, at least a fair percentage. But then I pick up something like Thomas Cranmer of Canterbury, and I only understand maybe 60%. That’s frustrating. Yes, it’s partly me: I’m not the brightest lightbulb in the chandelier. And maybe if I kept it up for the next 10 years, reading every book he ever read, studying the philosophers and church fathers/mothers he most loved, and getting myself initiated into a Rosicrucian secret society, then maybe I would understand.

But it’s not all me. There is an awful lot of that needless obscurity, for which C.S. Lewis scolded him, in Williams’s works. And I don’t think that a reader should have to go through that rigorous training I described above in order to enjoy a book. I don’t mind difficult, but this is near impossibility. That’s frustrating.

And the continuing revelations about his shady life, tweeted out day by day by @GrevelLindop, are also disturbing. How dare this guy call himself a Christian and set himself up as an example, a teacher, a “master” of disciples, and then continue on in his philandering ways? What’s worse is that he worked his sins into his theological system in such a way as to persuade himself (and some others) that his vices were actually virtues. That’s far worse than confessing them and getting on with sanctification. I know that’s a separate question from pure literary criticism, but it’s frustrating to me.

I’m not giving up. I just might make it through his works within the next year. There are quite a few left to go—26, by my count—but lots of them are plays and most of them I have read before, so I should be able to do it. Then I’ve got two or three chapters I’ve said I’ll write about him for various collections, and a keynote speech about him to give—and then maybe I’ll give him a rest for a while. That might be good. Maybe I can go away and study some other big topics in British Modernism, and/or Arthuriana, and then come back someday smarter and more patient, and annotate his poetry.

I’m not giving up. I just might make it through his works within the next year. There are quite a few left to go—26, by my count—but lots of them are plays and most of them I have read before, so I should be able to do it. Then I’ve got two or three chapters I’ve said I’ll write about him for various collections, and a keynote speech about him to give—and then maybe I’ll give him a rest for a while. That might be good. Maybe I can go away and study some other big topics in British Modernism, and/or Arthuriana, and then come back someday smarter and more patient, and annotate his poetry.

What do you think? Good plan??

Ganbatte!

You seem the sort of person who would hate to leave something unfinished, especially when you are close to the end of it. And then, when you do finish, you can sit back with a much deeper level of satisfaction. But that’s just an impression. Only you know if your frustrations are doing harm, and if they are, then it’s time to step back now before it gets worse.

LikeLike

Yes, I shall persist. But what would “finished” be in this context? Reading and blogging about all his books; OK. Understanding all his books? Probably not. Doing “all” the necessary scholarship so everyone else can understand all his books? No way!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lol! I see your point. Still, what does “finished” ever mean? Eventually, one always has to say “good enough” and let go, aye?

LikeLike

Aye aye!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Approach him as an egg? If we can crack enough of the tough shell – go for ‘once over lightly’?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good plan!

You are probably already aware, but the last three–Elizabeth, Henry, and Stories–are available as Kindle books from Apocryphile Press. I bought their edition of Outlines of Romantic Theology and it was very well made. I would happily gift them to you as a show of support for the blog if you’d like. That said, it sounds like you could use a break! The clinical detachment of Damaris Tighe circa “Lion,” chapter 1 has its benefits. 😀

For what it’s worth, your blog has enabled me to appreciate and respect CW’s work even when I (often) disagree with him. Had it not existed, the odds are I would have ignored him entirely or dismissed him as a crank.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, thank you! You are very kind and generous. But (sigh), I don’t think I can muster the energy to slog through 3 more biographies right now. Do YOU want to guest blog about one of them? (pretty please?)

LikeLike

I can’t blame you! I feel like I did in school when the teacher asks a question and you try not to make eye contact, but then you look up to see who she’s calling on and she’s looking right at you… 🙂 Sure, one won’t kill me, right? I’ll take on Elizabeth. (Just don’t ask for that scholarly paper on economics and CW that came up on Twitter a while back!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hooray!! That would be grand! <1000 words, conversational style, you know the drill.

LikeLike

It is interesting that Stories of Great Names was issued in two versions for two markets – with corresponding differences in content! In his customer review at Amazon, Richard Sturch writes of its being “originally written for an Indian readership.” But that, as far as I recall, was only true of one of the versions. He goes on to list the subjects of the Apocryphile Press edition as “Alexander, Caesar, Charlemagne, Joan of Arc, Shakespeare, Voltaire and Wesley”. But that would suggest that they have reprinted the version not intended for an Indian readership. As I remember it, the Indian-readership one had two differences, one of whom was Asoka – but I can’t recall (1) who the other was, (2) whether it was a matter of addition or substitution, and (3) where this is accessibly documented! (Not in Lois Glenn’s Checklist, alas.)

LikeLike

I have the Apocryphile Press edition as well as the OUP edition (fifth impression, 1946–first published 1937). The OUP one has the Price Rs. 2 on the cover and says on the verso of the title page “Printed in India from plates at the Good Pastor Press, Madras

(Paper issue card no. MS. 83) and published by Geoffrey Cumberlege, Oxford University Press, Madras (Paper issue card no. MS. 1) Dated 1-6-1946.”

The OUP edition also has on the title page “with notes by R. D. Binfield”, but the texts are identical so I wonder if there really were two versions. I hope you can remember where you saw this, David.

LikeLike

I can do a summary of “Rochester.” I am somewhat disturbed by the prospect of reading through it and I hope it will help me come to some conclusions about Williams as a writer.

LikeLike

I’d be disturbed by the 1000-word limit… (Bad Influence of Williams, reinforcing Existing Faults?)

It’s a thoroughly enjoyable book (as I remember it), with none of the really bawdy and/or pornographic stuff attributed to Rochester quoted.

(If you want to read further, I see Internet Archive has scans of a 1700 ed. of his Poems (together with those of Roscommon and Yalden: Rochester index on pp. 347-48), a 1714 ed. of his Works (title-page missing), the later 1732 “Fourth Edition” (“Table” of contents before p. 1: at page 28 of page-counter) and seven poems in Goldsmid’s Some Political Satires of the Seventeenth Century (1885), plus sixteen poems in The Pembroke Booklets “First Series”, IV (1906) – as well as various scans of editions of Glibert Burnet’s Some Account of the Life and Death of John Wilmot, while Project Gutenberg has a transcription of a 1718 ed. of Works.)

LikeLike

It’s good to know that Williams does not dwell upon the more pornographic elements of Rochester’s works. I’m not sure how to approach the work in light of the tidbit that @GrevelLindop posted this morning. It’s probably best not to fall into the personal heresy…

LikeLike

For those who missed it: Grevel tweeted:

“Charles Williams told Anne Ridler his 1935 biog ‘shall not be about John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester at all. It will be about me.’”

LikeLike

My sense (as I remember it) is that it was an interesting biography of Rochester, and a snapshot of the period, in the first place (I think I had run into the remark to Anne Ridler when I set about to read it). It would be interesting to try to test how far Williams seemed to be doing the two things – about Rochester and about himself – at once: though that might be better as a following step after a summary – ?

LikeLike

Another fun ‘post-summary’ idea might be for someone to compare C.W.’s Henry VII and the BBC Shadow of the Tower (1972).

LikeLike

That would be wonderful! Hooray!! That would be grand! <1000 words, conversational style, etc.

LikeLike

As to access, perhaps add a strand to the call… In nine-and-a-half weeks, with 1 January 2015, anybody who owns a copy of one of Williams’s books/texts published during his lifetime will, in a great many parts of the world, be simply legally able to scan it and circulate it as a file or put it online.

Could Williams-minded (in whatever sense!) folk – including the Wade, the Williams Society, the Inklings Gesellschaft, Michael Paulus, your good self (and so on) be encouraged to look into creating an online virtual Williams Library? (Maybe donating to the Internet Archive, whether ‘as well’ or ‘instead’, is also a good idea – but I don’t know how it works.)

Any similar approach to unpublished or posthumously published works is another story, which would depend on the Estate, and, variously, libraries and publishers.

Grevel’s biography is going to give us huge lots of new ‘material’ and ‘data’, and will take time to digest. For one example, do we – will we – know any more about a fuller ‘Mystery’ play from which the (selected?) “Scenes” were published in 1919? Was there one? If so, finished, or a work-in-progress? Extant, or presumed lost? This is both daunting and exhilarating – perhaps adds ‘pressure’ but also justifies relaxing and taking the time needed – even a leisurely pace.

LikeLike

“I want to grab my purple pen and fix up his works.” That will probably also be largely legal in a couple months (though checking with Georgia Glover about the details would be sensible). And it would be an interesting undertaking – say, an essay by way of experiment.

LikeLike

I think it’s a good idea to take a break. I read many other things than CW and sometimes don’t look at him for months. The problem with his ideas is that you have to be familiar with them before you can really read him so how do you read him in the first place? May I recommend Mary McDermott Shideler, who expounds them clearly, with plenty of quotations. I have never read the biographies, and don’t know that I am ever going to. I think we have to accept that a good deal of what he wrote is ephemeral and doesn’t need to be read. To understand the mature Arthurian poems, my great interest, you need to understand quite a lot of Arthuriana other than CW, but of CW himself, you can find most of what you need in The Descent of the Dove and The Figure of Beatrice, with occasional glances at the novels.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“And maybe if I kept it up for the next 10 years, […] then maybe I would understand.” To your possible encouragement or horror, my nearly forty years of experience suggest otherwise… (which is not to say I’ve done everything I here replace with […]!).

But I’m confident Grevel’s biography will help us all in many ways.

And I have found that Williams, like Lewis, is ‘centrifugal’, directing my attention to all sorts of interesting things – about which I do not have to agree with what he seems to make of them.

LikeLike

“What’s worse is that he worked his sins into his theological system in such a way as to persuade himself (and some others) that his vices were actually virtues.” Another sense of “So Sick of CW”?

This is a very important ‘matter’, also with respect to the Arthurian poetry – in how far is it true, what exactly is he – or may he be – ‘up to’? I think ‘winnowing Williams’ is worthwhile for any who feel so called – or simply realistically ‘up to’ it. But it should not be expected or asked of anyone. (When the magic sword stuff came out in 1983, I wasn’t sure what to do, and consulted with various people, including Dame Helen Gardner and Lyle Dorsett…)

LikeLike

“Thomas, Thomas, Anne is not what I thought.”

“Is your image broken Anne?”

Regarding Williams’s theologizing his lust, this reminds me of one of the patron saints of the evangelical left, John Howard Yoder. He did a similar thing with his own lascivious misadventures.

These revelations are not all that surprising to me, but they do mitigate my enthusiasm for Williams, new as it is. I was just discussing with some Roman Catholic friends of mine that I didn’t consider my mistrust of Williams’s ‘orthodoxy’ to be any real impediment to my appreciation of him. But what you have said here regarding his philandering definitely poses something of a stumbling block. The other things were fruit flies in the ointment, this is a housefly. Ever since I perused through Forgiveness of Sins years ago I have always looked on Williams’s theological ideas with some degree of suspicion. But now I feel just a little like the inimitable Edward Petherbridge (the TV Wimsey) seeing Mr. Urquhart’s arsenic for the first time, “My word . . . what have we here?”

Perhaps Tolkien was seeing in Williams’s influence on Lewis what Lewis saw in Steiner’s influence on Barfield. And it wasn’t just a petulant jealousy after all. It was discernment.

I’m sorry T.S. Eliot for saying Thomas Cranmer of Canterbury was more potent than Murder in the Cathedral. Can I come home now.

As for you Mrs. Higgins, get thee to a nunnery!

LikeLiked by 1 person

When, consulting her, I introduced Dame Helen Gardner to the magic sword stuff (etc.) in Mrs. Hadfield’s 1983 book, her reaction was something like ‘poor man!’ (which I did not take in any sense to exclude ‘poor young women!’).

I wonder what the full response of the former ‘Philomastix’ (as Lewis nicknamed himself in 1917 letters to Greeves) would have been, had he known the scope of the ‘darker sides’ of Williams?

Tolkien on Williams’s influence on Lewis seems a complex matter. For example, saying That Hideous Strength, under Williams’s influence, “spoiled” the trilogy, includes his calling the novel “good […] in itself”! (Letter 252). And what of the “witch doctor” characterization Humphrey Carpenter got from Paul Drayton’s recollection of a 1967 conversation with Tolkien (Inklings, pp. 121, 272: Part 3, Chapter 2, paragraph 6)? Has anyone followed that up with Paul Drayton?

LikeLike

Lewis’s response to William’s ‘darker side’ would have been quite interesting. Some of Lewis’s adolescent preoccupations enter into his later works, particularly “The Pilgrim’s Regress” (with then dragons on the Isthmus Sadisticus and the Isthmus Masochistus) and “The Problem of Pain”.

LikeLike

Yes, Lewis, and probably half of England had a spanking fetish. And if contemporary sexual statistics are to be believed, so does one out of every three people commenting on this blog. But let’s not weave a theological tapestry out of it. It is not Williams’s ‘darker side’ that troubles me. It is that he, like Yoder (former Notre Dame Theology professor), appears to have attempted to work it into some sort of Christian ethic.

As for Lewis’s ‘Philomastix’ reference, I have always found it rather amusing that Lewis detractors (not saying you are) have thought that that was some kind of big scandal or something. Like Philip Pullman waving it about in Christians faces as if he had discovered the very bones of the crucified Christ. I thought that was rather childish of him and quite wide of the point. That would be like trying to scandalize Paul’s Christianity with the fact that he once persecuted them, or to besmirch the character of mayor Valjean by squealing “but he stole silverware.” Remember that the sadist dominatrix in That Hideous Strength was a part of the hideousness. Lewis repented of sadism, and disavowed it in his writings. What we are dealing with with Yoder and Williams is a sexual misconduct that was never wholly repented of or disavowed, nay, it was theologized–and that is a real scandal. And it ought to give Williams admirers some degree of pause. I think the analogy of the tainted well has application here.

I also wonder what Lewis’s response would have been, and whether he did know the full scope of Williams’s darker side.

All that said, the chapter called “The Beetles” in All Hallow’s Eve” is one of the finest pieces of horror writing I have ever encountered. With John Howard Yoder, on the other hand, there is not a damned thing he ever wrote that would endear me to him. I still love Williams writing!

LikeLike

I think it very unlikely Lewis knew or even suspected “the full scope of Williams’s darker side”. I also think he could have commended what he thought good about Williams if he had know – as he did in various ways with Ovid, Shelley, Wagner, and William Morris, for example – but (as with them), he would have done it discernably differently. As you say, “Lewis repented of sadism, and disavowed it in his writings.” But that would probably have been a distinctive element in his response to Williams’s ‘darker sides’ – in which plural I include his appearing “to have attempted to work it into some sort of Christian ethic.” It was not just comparatively simple hypocrisy (if I may so put it), like that of the sub-Chestertonian dissertation subject in David Lodge’s The British Museum is Falling Down (to take an example that struck me when I read it). That, “never wholly repented of”, would have been grave and really scandalous in its own way. But this is something else – stranger, more elaborate, and more vexing to the admirer and scholar (as far as I can see, and have experienced it). The question of “the tainted well” (if I understand you correctly), is an important one. How has Williams interwoven things, and how can they be most serviceably disentangled? And, if Williams’s ‘magic sword (etc.) practices’ have been (as he seems to have thought) somehow instrumental in producing the late poetry, what are we to do about that?

(Incidentally, I feel pretty sure I read something of Yoder’s in a course by Dr. Joan Tooke (author of The Just War in Aquinas and Grotius, among other things), but would have to hunt it up and see how worthwhile or otherwise I thought it on rereading: I don’t recall any very strong reaction pro or con – assuming it’s Yoder’s book I’m remembering.)

LikeLike

It sounds like a good plan, and I’m glad you have the candidness and honesty to speak of it here. I hope that even after finishing your summaries of Williams’ books that you won’t give up blogging about literary things, but it needn’t be all Williams. I’ve only read a short story of his, in Douglas Anderson’s Tales Before Narnia, and didn’t really understand it. I’m open to reading more by him. However, what I’ve heard about his moral and religious beliefs (and his actions thereon) make me shudder. They’re not a barrier to reading his work, nor hopefully to appreciating any good that is in them, but they do harm my perception of him, just as my knowledge of Tolkien and Lewis’ lives enhances my appreciation of them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cool, David! You’re talking about this short story, right? https://theoddestinkling.wordpress.com/2015/09/02/to-try-to-save-the-devil/

I didn’t know about that collection.

LikeLike

I wouldn’t think that was the easiest introduction to Williams, either – your linked review shows an admirably careful response in the circumstances. As a lover of Arthur Machen, Ambrose Bierce, Algernon Blackwood, and M.R. James, if that had been my first taste, I don’t think I would have responded with equal discernment. I’m still glad I happened to start with War in Heaven. You might like to try War in Heaven followed by Many Dimensions, which is a sort of sequel in at least one particular (a sort of prophecy from the one fulfilled in the other) – as well as the major appearance of Lord Arglay, making the short story a kind of pedant of it (though I don’t know that in any significant way illuminates the short story!).

LikeLike

That’s the one! You speak rather highly of it, so perhaps I’ll have to give it another read (or listen, as the audio recording sounds like it could be helpful).

LikeLike

I presume you have already done CW’s “Seed of Adam: A Nativity Play”? I have just found it in a September 1937 copy of the journal “Christendom”. Williams observes that “it has been enlarged (from its previous performance in Hornchurch, Christmas 1936) for the London presentation in November (1937)……at least one alteration was required by the Censor before production.” One wonders what was censored. In her “Notes and Comments” in the same issue Ruth Kenyon describes it as “a genuine work of Christian art.”

LikeLike

I can’t remember what was censored, but think ‘we know’ – maybe it’s discussed in Seed of Adam and Other Plays (1948) or Collected Plays (1963).

Sørina has not yet posted about it, but it may well come under her saying “There are quite a few left to go—26, by my count—but lots of them are plays and most of them I have read before, so I should be able to do it.”

It certainly rewards attention, and may be controversial today for some of the same reasons as well as for different reasons as in the late 1930s. (St. Joseph as a a young Moslem soldier, for instance?)

It is interesting to read around in the journal “Christendom”, in general as well as for Williams (whose earlier versions of late poems appeared in March 1938 and “The Recovery of Spiritual Initiative” in December 1940).

LikeLike

Maurice Reckitt, the editor, has a little Wikipedia article, but the journal “Christendom” doesn’t have its own – I don’t know where online is best to find out more about it.

LikeLike

I’ve looked up the 1948 volume, in which Raymond Hunt notes he has prepared the second version for it, which differs from the first version, in Christendom, and adds “in performance one alteration was required by the Censor.” He does not, however, say what or indicate it in the text. As I remember on rereading, it is when Adam “re-enters as AUGUSTUS” and describes himself as “the power of the world, from brow to anus” (riming with “Octavianus” two lines earlier): “anus” was the censored word. (But I can’t recall where I know this from!)

LikeLike

Nope; I’m going through chronologically, and I’m in 1935. You can see the index here: https://theoddestinkling.wordpress.com/index-2/.

LikeLike

Maybe absence will make the heart grow fonder?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Let’s hope so! 🙂

LikeLike

@Sorina – I am very sympathetic to your situation. For myself, I have been dipping into CW at a very relaxed pace, on and off, over nearly thirty years – as and when it pleased me.

I react badly to having the pace of my reading forced, or being in a situation when I must read such and such a book *now* – I seldom enjoy books read under such pressure, and it often turns me against them. This pretty much renders me unsuitable as a teacher or student of English Literature – where one is expected to read ‘to order’ and produce an ‘appropriate’ response – and I have remained happily on the sidelines.

I began reading CW while I was working on a Masters by thesis at Durham University (England) on the modern Scottish writer Alasdair Gray (who happened to be a friend) – but I overdid AG my immersion in AG over the next couple of years, and have almost never read his work since!

I personally am grateful for your work on CW and have benefited from it in lots of ways; but you should not feel obliged to keep plugging-away, on and on – or you will inevitably lose that freshness and spontaneity of response which was an important part of what you brought to CW studies!

But perhaps, like me, you will find a new stimulus in grappling with the detailed overview in Grevel Lindop’s biography – I find myself almost feeling as if I know *less* about CW than before I read the book, and grappling to try and make sense of him even more than before! I think you have flagged-up, above, some of the major issues which emerge: e.g. core motivations of the man, the wilful obscurity, and the sense that his theology is a ‘rationalization’.

Because Williams’s Christian insights cannot (or at least should not) quickly be dismissed – not when so strongly endorsed by the most important Anglican lay thinkers of his era – CS Lewis, TS Eliot and Dorothy L Sayers – all of whom were friends and knew him and his work in great depth.

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Bruce! It’s OK; I don’t mind reading to a forced schedule. In fact, that’s probably the only way I get my most valuable reading done. I love being a scholar and teacher and so am quite happy reading to a forced schedule all my life. There is no way I would read straight through CW unless I “had” to do so. AND…. I’m hoping to make some pretty exciting, significant changes in my life over the next year or so (we’ll see), so I’d like to get CW done by then. So, I shall press on! Many thanks, though, many thanks.

LikeLike

Some sickening news:

http://anglicanink.com/article/former-bishop-chichester-acknowledged-have-been-child-sexual-abuser

According to his Wikipedia article, “From 1925 to 1929, Bell was Dean of Canterbury. During this time, he initiated the Canterbury Festival of the arts, with guest artists such as John Masefield, Gustav Holst, Dorothy L. Sayers and T. S. Eliot (whose 1935 drama “Murder in the Cathedral” was commissioned by Bell for the festival).” Williams’s Cranmer was the festival play after Eliot’s and followed by Sayers’s The Zeal of Thy House: the Wikipedia article, “List of plays by Dorothy L. Sayers”, says, “Sayers had been recommended to Babington by the Festival’s playwright of 1936, the poet Charles Williams.”

LikeLike

A response worth reading by Peter Hitchens published today includes:

I was aghast to read in several newspapers (two of them supposedly conservative journals of record) that George Bell ‘was’ a child abuser. Not ‘allegedly’ but ‘was’. The Church was also said to have ‘admitted’ or ‘acknowledged’ the dead Bishop’s guilt.

Well, nothing is impossible. But the alleged offence took place more than 60 years ago, and wasn’t alleged until 1995 (when he had been dead for 37 years). One report complained it hadn’t been referred to the police at the time. What were they supposed to do? Exhume him and question his bones?

As usual, we may not know the name or sex of the accuser, though money has been paid to him or her in compensation.

But there has been nothing resembling a trial. No evidence has been tested. No defence has been offered. No witness has been cross-examined. No jury has given a verdict. Yet this allegation is being treated as if it was a conviction. Once again I see the England I grew up in disappearing. What happened to the presumption of innocence and the right to a fair trial before a jury of your peers?

I know the C of E has had real problems with child abuse in recent years, and has a lot of apologising to do. No doubt. But was it wise or right to sacrifice the reputation of George Bell, to try to save its own? Who defended the dead man, in this secret process?

As the prophet Isaiah once remarked: ‘Judgment is turned away backward, and justice standeth afar off: for truth is fallen in the street, and equity cannot enter.’

This is why I continue to believe there is one court of justice where no lies can be told and all secrets are revealed. I’ll leave the final appeal to a higher authority than Lambeth Palace.

LikeLike

Yes that is sickening. And since we are flinging wide the curtains, I just learned of the Marion Zimmer Bradley scandal. Turns out that this feminist fantasy icon neo-pagan had been trying out some of her ‘anarchist sexuality’ on her own daughter, Moira Greyland between the ages of 3-12 years old; not to mention what her eventually incarcerated husband, Walter Breen, had been doing to Moira and little boys (he raped her), apparently with MZB’s knowledge. Given MZB’s connection with sorcery and paganism, I couldn’t help but recall one of the most arresting lines from William Morris’s Well at the World’s End. Recounting to Ralph her childhood years held in “the thrall of the sorceress” the Lady said: “But about this time my mistress, from being kinder to me than before, began to grow harder, and ofttimes used me cruelly: but of her deeds to me, my friend, thou shalt ask me no more than I tell thee.” Oh the weary world. And here is a passage from the Washington Post: “A significant theme of Zimmer Bradley’s answers in her 1998 deposition is the idea that very young teenagers ought to be able to make their own sexual decisions, including about whether to have sex with adults who proposition them. She rejects the idea that any element of coercion is possible in these interactions, particularly when a teenager is physically larger than an adult.” When I first began to read into this, I had thought that her misdeeds were aberrations from her ideals but it turns out that they were to a fair degree born out of her ideals.

LikeLike

But these only set the star of Bethlehem in greater relief. Quoth Eliot, Julian of Norwich: Sin is Behovely, but

All shall be well, and

All manner of thing shall be well.

LikeLike

The latest state of the discussion concerning allegations and C of E monetary settlement and statements with respect to Bishop Bell:

http://hitchensblog.mailonsunday.co.uk/2016/02/in-tywo-minds-the-strange-position-of-the-bishop-of-durham.html

Mr. Hitchins’s blog looks like someplace where one can continue to discover updates and discussion.

LikeLike

A more recent state of the discussion worth noting:

http://www.georgebellgroup.org/

LikeLike

And another:

http://hitchensblog.mailonsunday.co.uk/2016/03/murder-in-the-cathedral-the-casual-wrecking-of-a-great-name.html

LikeLike

A year later, Peter Hitchens has written an evocative, but also polemical, reminiscence of and reflection upon his “time as a non-singing pupil” at the Chichester Cathedral choir school:

https://www.firstthings.com/article/2016/05/a-church-that-was

He does not give the exact dates of his time there, but it is worth noting he was born five-and-a-half years after the death of Williams, and before Lewis had collected his broadcast talks as Mere Christianity, and just under a fortnight after the second Narnia book appeared.

LikeLike

Since I first brought the Bell-accusation news here, I wanted to add another update, which strikes me as clearly very important:

http://anglican.ink/2019/05/15/call-for-the-church-of-england-to-repent-over-its-slander-of-george-bell/

It is probably also worth underlining that the noted Williams scholar, the Rt. Rev. Dr. Gavin Ashenden, has been very active in the George Bell Group, seeking clarity and justice.

LikeLike